An impact report describes why your efforts and outcomes are relevant and important. It describes what difference they are making. It answers the questions:

- Why does this matter?

- How is it making a difference?

- Who or what is being affected?

- What part are you playing?

Your impact report should include a description of:

- The issue or problem.

- Why it is important to address this issue or problem.

- The action you have taken, are taking, or intend to take to make a difference.

- The outcome or intended outcome.

- The difference being made, including who benefits and in what ways.

- Your role and why it is important to the outcome and impact.

- The collaborators and others who have contributed to the impact you are describing.

12 Tips for Writing a Good Impact Report

- Approach this as an opportunity for others to understand rather than for you to explain.

- Keep it short.

- Use short sentences (no more than 30 words) and paragraphs (3-5 sentences).

- Write to the audience. Assume your audience includes people outside your discipline (it does).

- Briefly describe jargon and acronyms or avoid them altogether.

- Limit the description of the method you are using to a few non-technical sentences.

- Make sure the difference is evident.

- Include the human story behind the science (Why is this making a difference for people?)

- Clearly describe how your contributions contribute to the difference being made.

- Use numbers to illustrate increases or decreases that make a difference.

- Use anecdotes sparingly to bring life to other evidence of impact.

- Proofread (you and someone else) for typos, grammar, readability, and understandability.

Impact Framework

Using the following framework may help identify impacts of your work and accomplishments1. You do not need to identify the dimension of this framework in your impact report.

- Research-related impacts. e.g., new research methods or approaches that are leading to new discoveries; changes in how research is conducted by others.

- Policy-related impacts. e.g., changes to governmental policy or industry standards; changes to professionals standards.

- Practice-related impacts. e.g., teaching pedagogy was improved; Extension practices were modified to reach new audiences; industry practices were changed.

- One Health-related impacts. e.g., disease tolerance was increased; plant, animal, or human health was improved; crop nutritional value was increased.

- Natural ecosystem-related impacts. e.g., improved use of natural resources; increased balance in land-use.

- Society related-impacts. e.g., improved community vitality;

- Economic-related impacts. e.g., increased profitability of farming or ranching; greater opportunities due to job growth.

Other Resources for Writing Impact Reports

Watch Recorded Impact Writing Workshop IANR Writing Workshop Packet IANR Writing Workshop Slides

Those looking for additional guidance on writing impact reports may want to consider the Multistate Research Fund Impacts web site. This site includes a useful infographic and worksheets and examples.

While you will provide your impact report in writing, a verbal example may help to illustrate impact reports. See how Emily Johnston punctuates the impact of her research in just three minutes. Note how she exemplifies each of the elements of impact reports identified above.

Impact Report Examples

Consumer and economic impact: Leaf minor insect expertise

Guatemalan snow peas were detained at US ports of entry because of infestation by an unknown leaf miner species. In its larval stage, a leaf miner lives in and eats the leaf tissue of plants which can result in reduced yield. Fear arose that this unknown species would be imported to the US and infest US-grown crops. Guatemalan small farmers lost almost $5.7 million in revenue due to this detention. Others in the supply chain also lost revenue. US consumers lost access to off-season high-quality, affordable snow peas.

In response to this crisis, I provided technical assistance to the Integrated Pest Management Collaborative Research Support Program (IPM CRSP) team. IPM CRSP was dispatched to the Guatemalan highlands to complete a taxonomic survey of snow pea leaf miner insects. This survey found the Liriomyza Huidobrensis, a major leaf minor species found in snow peas and other export crops. This species is also already found in the United States.

As a result of the IPM CRSP team’s efforts, which included my contributions, Guatemalan snow pea imports were resumed. US consumers regained year-round access to high quality snow peas. The IPM CRSP effort had positive economic impacts on the entire product chain in both Guatemala and the US. The US market of Guatemalan snow peas is about $140 million, of which about $7 million (5%) goes to the producer.

Community vitality impact: Rural mental health

Despite advances in the treatment of mental health problems, incidence rates are increasing. Rate increases are especially pronounced in rural communities where individuals and families are less likely to have access to affordable specialized care. Suicide rate is an indicator of the prevalence of mental health problems. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), suicide rates in rural areas of the US increased 46% between 2000 and 2020 whereas in urban areas the increase was 27.3%. In Nebraska, 85 of 93 counties are designated as mental health professional shortage areas. Twenty-three counties have no mental health care providers. Solutions to the crisis in rural communities include a) access to acceptable mental health care, b) awareness of the problem, c) the development of local preventative strategies. The work of me and my collaborators address all three solutions.

To build local capacity, my collaborators [names] and I identified three rural Nebraska counties to partner with in research that would have local impact. Each had one or more medical providers and no more than one mental health provider practicing within the county. Through Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR), problems affecting the local community were identified, research questions that community members cared about were formulated, relevant data was gathered, and actionable results were generated. As a result, community members leveraged local resources to develop programming that would raise awareness of mental health problems and structures to support favorable mental health outcomes. They each made arrangements with mental health care specialists outside the community to provide telemental health services through the local medical clinic, thereby increasing local access to care.

This project had demonstrable societal and health impacts. Pre-engagement surveys indicated that approximately 1 in 5 (19%) adults had basic awareness of mental health problems and as few as 1 in 8 (12%) felt comfortable talking with a professional about it. Post-engagement surveys indicated that basic awareness and comfort talking to a professional rose to almost 1 of 3 (31% and 29% respectively). Sadly, within 3 months after our engagement ended, one community experienced a suicide. As a result of their participation in the project, local community members were well positioned to respond. Those who had participated with us in CBPR came together to develop a community response that would raise awareness, address grief, and provide support. They implemented a response that made a difference within their community.

Implementation of Best Practices Impact: Soil Health Networks

Public Value. Productive, sustainable, and resilient agriculture is dependent on soil health. Agricultural land-use practices can either degrade or improve the condition of the soils in a way that has long-term consequences. Producers can manage soil health through practices that maximize water infiltration, reduce soil erosion, and improve nutrient cycling.

The Situation. Getting evidence-based information and practical strategies to producers is important to nurturing healthy soils. But, often this isn’t enough to change behavior. Opportunities for producers to talk with, learn from, and encourage and support each other increase the likelihood that soil health practices will be used. Traditional programming that relies on formal presentations to large groups, while efficient, does not lead to the discussion, sharing experiences, and networking that encourages adoption of practices.

Extension Response. I partnered with Alexis Myers from the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to develop the Extension Soil Health Café Talks. The Café brings together people who are invested in improving soil health outcomes (e.g., producers, Extension faculty, scientists, industry representatives, consultants). It is a way to share scientific information and practical solutions in a small-group community-like setting that facilitates attendees networking with each other.

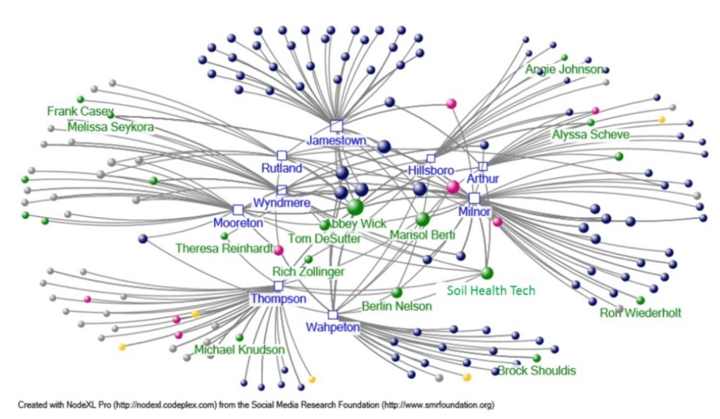

Impact. The Extension Soil Health Café Talks increased the reach of Extension faculty, consultants, and farmers by expanding their networks. The more the network expanded the greater the influence that person had on soil health practices. Over a three-year period (2021-2023), the team implementing the Cafés consisted of seven farmers, seven Extension faculty members, and four consultants. The Cafés led to 362 connections among 169 individuals. As the following network graphic illustrates, those with more direct and indirect connections had more influence on on-farm practices. The green (Extension faculty member), blue (farmer), and pink (consultant) circles represent Café team members. The size of the circle and the location within the network graphic indicates their influence on others in using evidence-based soil health practices. These connections facilitated by the Cafés expanded the network and influence of individuals on the use of research-based soil health practices in farmers’ fields.

Participant Feedback

“This is a model extension program. I can’t think of a better way to engage with farmers.” – team member consultant. “I enjoyed talking with other growers and learning how they are managing their soils.”

– Participant farmer

1 Modified from https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-6-134